The Bookshop Podcast

The Bookshop Podcast

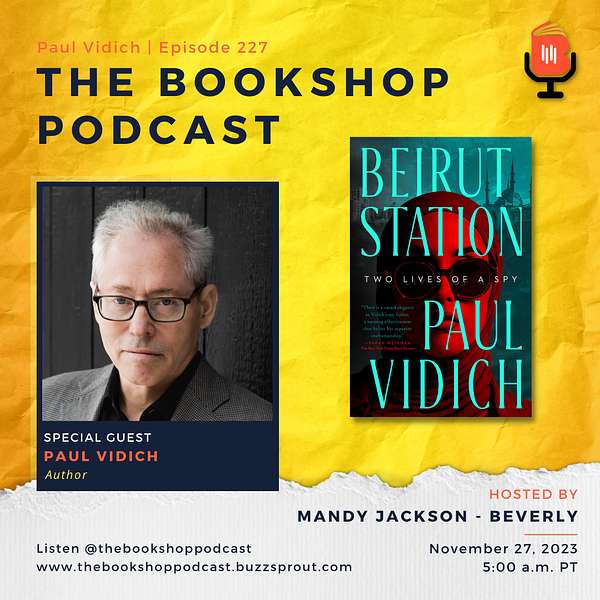

Discussing Ethical Dysfunction in Literature With Author Paul Vidich

Ready for a deep dive into the world of writing and publishing? Join me as I chat with author Paul Vidich who traded his corporate media suit for a writer's pen. We'll traverse through his personal anecdotes revealing the inspiration behind his latest novel, Beirut Station. Vidich shares the artistic process behind the book's cover design and we discuss Erroll Morris's newest documentary, The Pigeon Tunnel.

In the same breath, we gear up to navigate the labyrinth of ethical dilemmas in cultures and organizations. Are you a fan of espionage novels? Well, buckle up as we decipher the moral grey areas and high-stress environments faced by the characters in Beirut Station. The conversation extends to the complexities of the publishing industry, reminding us of the crucial role that indie bookshops play for authors and readers alike.

Paul Vidich

The Pigeon Tunnel, Errol Morris

Wormwood, Errol Morris

Beirut Station: Two Lives of a Spy, Paul Vidich

The Peacock And The Sparrow, I. S. Berry

The Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia Highsmith

Hi, my name is Mandy Jackson Beverly and I'm a Bibliophile. Welcome to the Bookshop Podcast. Each week, I present interviews with independent bookshop owners from around the globe, authors and specialists in subjects dear to my heart the environment and social justice. To help the show reach more people, please share it with friends and family and on social media, and remember to subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to this podcast. You're listening to Episode 227.

Speaker 1:Paul Wittig is the author of six novels, his latest being Bay Root Station, published by Pegasus Books in October 2023. His previous novel, the Mercenary, was selected by Crime Reads as one of the top ten espionage novels of 2021. His debut novel, an Honourable man, was selected by Publishers Weekly as a top ten mystery and thriller novel in 2016. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, lit Hub, crime Reads, the Fugue, the Nation Narrative Magazine and elsewhere. Wittig received his MFA from Rutgers-Nuik and he was the co-founder and editor of Storyville.

Speaker 1:Prior to turning to writing, wittig had a distinguished career in music and media at Time Warner, aol and Warner Music Group, where he was executive vice president in charge of global digital strategy. He was a member of the National Academies Committee on the Impact of Copyright Policy on Innovation in the Digital Era and testified in Washington before rate hearings. He presently serves as an independent board director, angel investor and advisor to internet media companies in video and music. He is a graduate of Wesleyan University, where he was a trustee and received a Distinguished Alumni Award, and the Wharton School University of Pennsylvania. He serves on the boards of directors of poets and writers, the new school for social research and the Elizabeth Kostovar Foundation. Hi, paul, and welcome to the show. It's lovely to have you here.

Speaker 2:Well, thank you, I'm delighted to be here.

Speaker 1:When I'm asked to interview authors, I look for threads, something that we might have in common, and what I found with you is and we will be talking about your story involving this particular person a little further into the interview but my husband worked with Errol Morris for years.

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's an interesting connection. I mean I've just seen his new movie, the Pigeon Tunnel, which is wonderful, and I met Errol and provided some background for his documentary on my cousin Eric Olsen and Frank Olsen, and so I know him a little bit personally, but he's in a remarkable filmmaker for sure.

Speaker 1:Yes, he is, and I agree with you. The Pigeon Tunnel is fantastic. You and I were talking earlier about the gorgeous cover for your new novel, bay Root Station, so can you talk about the cover and specifically the colors used by the designer?

Speaker 2:Well, the graphic artists had read the book and he knew it was in Bay Root and Bay Root at the time, in 2006. There was a war going on and I think the red in the cover speaks to the heat of the plot of the story. But at the same time he uses this wonderful green, which is the color of Islam, in the back on the cover you see, I think, a mosque, the minarets. So I think he, together with the photo of the woman on the cover, it really evokes the elements of the book very nicely.

Speaker 1:Yes, it does. When I first saw the cover and that scarlet red color, I immediately thought of Mary Magdalene. Now, I'm not a religious person, but that color is often associated with her and for me, I think of a strong woman which, after reading the book, is apropos. Anyway, moving on, let's begin by learning about you, your business and media work and your dedication to writing, which started way before you penned your first novel.

Speaker 2:Well, like so many people, I left college, came to New York and didn't have a good idea of what I wanted to do with my life. But I sort of had the idea I would get into film, but there was no film going on in New York. So I thought, well, maybe I'll write a script. But I didn't know how to write a script. So I thought, well, maybe I'll write a novel and turn it into a script, which is a very convoluted way of grasping for straws about my young life. And, of course, in the midst of that I met a woman who became my wife and the mother of our two sons, and I had the responsibilities of helping raise the family and I required rent money and all the other things that go along with just life. And so, and I wasn't confident enough about myself as a writer to write, so I went off and got a business degree and sort of put my writing on hold. I sort of mothballed my passion for storytelling. But I made a contract with myself, which was that when I was financially able to give up my career in media, I would then go back to writing a novel and trying to pursue a career as an author. And that happened in my mid fifties. So I woke up at one point and said you know, this is about the last moment in my life that I'll be able to call on that young dream that I had. And I surprised a lot of my friends at AOL, time Warner, because I had a big contract, I was a big executive. They said why are you doing this? Do you think you actually will be able to succeed as a writer? And I said, well, I don't know, we'll see.

Speaker 2:But then, of course, I then got an MFA and pursued basically 10 year. I guess it's sort of the things you do when you're getting off in a career. It's the 10,000 hours that Malcolm Gladwell talks about to be good at anything. And you don't really think about it when you start because if you did think about it you probably wouldn't do it. But in my case I did. And then my first novel was published at the age of 65. Now this is my sixth novel. So I'm a poster child for all those later aged writers who wanted to write but haven't found the time or didn't have the wherewithal to do it. But it's a great thing to be able to write, to tell a story, and I'm very happy that I did make that choice.

Speaker 1:Getting back to what you said earlier, I think there's a lot to be said for waiting until you're older to write and you're at an age where you can look back and think of all the things that kind of led you to that point and you have this vast vault of knowledge that you can put into your writing. It's amazing what time gives us as we get older.

Speaker 2:I totally agree. The novels I would have written as a young man would not have been the novels that I have been writing, because I think the wisdom that you get through experience and the knowledge you get by having lived help shape your view of the world. In my case, I would say that my view of the world, my moral view of the world, was shaped by a variety of things that I witnessed, and if I had not had that experience, I would not be writing the novels I'm writing now and I think it absolutely is the case that you mature and with that maturity you have a deeper sense of gravity about the world.

Speaker 2:So my novels are sort of thrillers, but they're really not.

Speaker 1:Well, there's a lot going on in Beirut Station and it is bound around relationships, which I love in a book, and I think the emotional aspect of writing about relationships is something that comes with maturity and age and, as you said, if you were to have written about Annalise in your 20s, she wouldn't have had the depth that she does in Beirut Station. She's a complicated character, which makes her fascinating to me. While I was reading Beirut Station, I wondered about the amount of research you must have to do to write your books. So can you walk us through your writing process from idea, research, character analysis and the actual but in the chair, writing?

Speaker 2:I do a lot of research and the first thing that I do after I finished one book is I sort of fall into this void, which is what's next? And in my case I don't have, for the most part, continuing characters, so it's not like I'm going to pursue something from a character that I've used in the past and I've, for the most part, set my novels in different places, but generally I start with setting. Writing is this stage? It's a place in which people find themselves for a reason and if you look at what drew them to that place, you begin to uncover their motivations and the conflicts and a story, and in my case, beirut was sort of a place that came to me.

Speaker 2:I read Ian Fleming's nonfiction account called Thrilling Cities, where he'd been sent around the world by the times to write chapters about cities that were of interest to him, and there's one on Beirut. So he did this in the 1950s and the 1950s Beirut was a particularly interesting place. It was sort of the Paris of the Mediterranean. It was a city that attracted a lot of intellectuals, a lot of the people who left other parts of the Middle East and were looking for a place of culture and free expression, and it was also a listening post for the CIA and for MI6. And it was a city where Kim Philby lived for about eight years before he defected to Moscow. It was a wonderful city, very evocative, and then the question became so who would be there? And sort of simultaneously because in some ways these things happened in my imagination at the same time and they may not be related but they sort of converge on a story At the same time I was very interested in this whole notion of extrajudicial execution, which is where a state without a court authority decides they want to assassinate somebody who's an enemy.

Speaker 2:So Jamal Khashoggi is an example of extrajudicial execution. And that notion was an interesting one because it sort of implies the question of who has the right to kill somebody. In a country like ours, where you've got a set of laws, it's the courts. There's a crime, there's evidence, there's a conviction, then there's a death penalty. But in the world of spies, where you're living beyond boundaries, beyond borders, where no one law of nations exists, people, presidents or other people can make the decision that this person, this terrorist, is a really bad guy. And that idea interested me and it so happened that that sort of led me to this character in the novel, who's based on somebody by the name of Imam Mungani, who was a Hezbollah terrorist and he had been behind the execution of the CIA chief of station in Beirut in 1985, guy by the name of William Buckley, and the CIA and Mossad spent 22 years tracking down Mugane and then killed him. He happened to be assassinated in Syria, but all of that sort of circulated in my imagination and at the same time I was reading about young women who had joined the CIA after 911, who found themselves in the Middle East, and I was drawn to the idea that there was a young woman who was operating on behalf of the CIA and struggling with some moral choices about the work that she was doing.

Speaker 2:So it's a very messy process. It's not one that's sort of linear. It's not like I say I'm going to do this. It's like I spend six months of research and the research is really going from one idea to another, picking up something that's of interest, and then following that thread and ultimately begin to create a storyline and with the storyline come characters, or it may be that the character comes first and the storyline follows, but at some point it feels good, it feels comfortable. It feels like there's enough there to support a novel.

Speaker 2:And when I get to that place then I begin to write dossiers on the characters, so I know as much as I can about them, so they're sort of intimate with who they are.

Speaker 2:And then I begin to organize the novel, the story of the novel, and I do a pretty comprehensive, basically, outline of each chapter.

Speaker 2:So this book, I think the 34 chapters, so I had a 60 page outline that included a lot of what was going to happen in each of the chapters and it's sort of when I get to that place I feel comfortable that I know the story I want to tell. That's when I begin writing the first draft. But of course in the writing of the draft things change. Characters decide that they don't want to be the character I thought they were going to be, and it's in that process that you become comfortable with the emotions of the characters and the relationships between the characters. And so the outline really is just a way of approaching what ends up becoming the novel. And for the most part I know where the novel is going to end before I started, because it's sort of like a North Star. You can navigate towards it and it sometimes changes. But what really changes is the stuff in between how you get there, not so much where you're going.

Speaker 1:So, with this in mind, who were the first characters who sprang to life during the initial idea stage of Bay Root Station? And was Annalise there from the beginning or did she appear later?

Speaker 2:She was there pretty much from the beginning.

Speaker 2:As part of my research, I had read memoirs by a number of young women who had joined the CIA after 9-11.

Speaker 2:And who wrote memoirs of their experience of being in the Middle East in the CIA, operating in non-official cover capacities, and they were very compelling stories.

Speaker 2:Young women who had joined the CIA after 9-11, who were full of the spirit of patriotism that was around at that point in time. And then their work in the field led them to other feelings. They witnessed the brutality of the region. They witnessed their own, what I'll call the claims on their idealism which they confronted the citizens, some of the people in the business, and it led them to their own sort of, I guess, moral crisis. And I thought well, that's interesting, because that's sort of the internal conflict that to me became very interesting to put Annalise in this place, where she's given a mission which tugs at her own sense of morality but at the same time has a commitment to the good work of the Central Intelligence Agency. And I think all great fiction comes out of conflict, personal conflict and how people navigate through it. So for me it was this character, annalise, this sort of an amalgam of the number of memoirs that I read.

Speaker 1:That were all very compelling and that's a good segue into my next question, because I was wondering if you could expand on ethical dysfunctionality in cultures and organizations and what draws you to this topic in your novels. You've covered that a little bit, but I was wondering if you could go a little deeper, because it does come up in your novels.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I think the origin of it is this personal story that I have, which is the story of my uncle, frank Olson, who worked for the CIA, was involved in bio weapons research and was involved in some very nasty stuff, and yet it troubled him deeply and so he found himself doing work that he didn't believe in. But he couldn't talk to his colleagues about the work because to do so would be to appear disloyal, and he couldn't talk to his wife about his work because it was top secret. So he was sort of cut off, struggling with his own moral questions. And the CIA recognized this and he was given LSD. At that time they thought it was a true drug and made him unstable. And a guy who is unstable, with state secrets in his head, what do you do with him? In Russia? You send him to the gulag. In his case they threw him out a window, the 13th floor of the Stoutwood Hotel.

Speaker 2:And that character the sort of person who's struggling with a problem within an organization where he can't talk to his wife about the problem and he can't discuss the problem with his colleagues that became very interesting to me because it raises all these questions, the moral questions of you know. Am I doing the right thing and how do I go about, you know, putting those questions to bed for myself. And in the CIA it's a particularly difficult thing because the nature of the work and the nature of the risks and the consequences of sort of being a somebody who speaks out are very real. And so in some ways, having worked in corporate America, you know I dealt with a lot of things but I didn't have to deal with that level of compromise. But on the other hand, you're always in a corporation or anywhere, you're always sort of putting on a face. You know there's the face of you go to the office and you're doing things with other people and sometimes you look the other way and sometimes you don't.

Speaker 2:But the nature of the choices you're making, if you're working in an intelligence agency, are much deeper and with greater consequence. So it was that question really that I have explored in different ways in different novels, the question of the gray areas that you live with. The gray-tone world of, you know, the shadow world of the spy is interesting for that reason Because it really highlights these types of choices where there's a conflict between the personal, moral, ethical person and the difficult, sometimes unethical work that is required of the job you're doing and that, to me, is sort of the best spy fiction. Joe Cannon, graham Greene, le Carré, all in one way or another way deal with this sort of moral choices that are sometimes very difficult by its, you know, in its protagonists.

Speaker 1:I often wonder how the heck do these agents keep these secrets and lies? I mean, do they have a panel of psychologists who they're able to pick up the phone and chat with or go and see within the agency?

Speaker 2:No, and so a couple of things that sort of indicate the stress that these people live under. And it's a particular type. The agency has a lot of different types of people, but there's an area called the directorate of operations, which is what we normally think of as spies, people who go overseas, who are operating, you know, undercover and trying to recruit assets. Among that group of people the divorce rate is something like 75 or 80 percent, very high, and there's a very high level of alcohol and drug abuse, you know, and both those two things are indicators of the stress that they live under. And the CIA recognizes this. And they do have trained psychologists who, you know, help these people through issues.

Speaker 2:I mean, for example, you know, in my case, annalise, you know, one of her jobs was to look over and over again at the beheading video of somebody who'd been captured in Iraq, and you can imagine the stress that puts you under and you know she created nightmares for her. But in the real world those are issues that create a lot of stress for these agency employees and the CIA has, you know, very quietly developed a, you know, an approach to helping them deal with these issues, because all of these people are like you and me. They went to college just to chose this career, but they have all of these same issues, fears and the same motivations that we have, just that they find themselves doing difficult work. The men and women I've met, you know very talented, very intelligent, very dedicated to their work and sometimes very conflicted about what you know what they're doing. But that, to me, makes them interesting characters.

Speaker 1:Circling back to your uncle, I can't imagine going through everything he went through and then being given LSD.

Speaker 2:Yes, it was a trauma for, you know, certainly the family. And you know, I do know I mean this is a bit of a decoration, but in 1953, I was three years old, our two families were very close and we have a house and a cabin in the other index. And when all of this about Frank Olson came out, I sat with my father and asked him, you know, what did he remember? And he said well, that's summer. Frank Olson died in November and that summer, the August of 1953.

Speaker 2:He and my uncle, frank Olson, were on the roof reshingling the roof and Frank was somebody who was sort of the hell fellow, well-met type, you know, told a lot of jokes, but that summer he was very sort of withdrawn and he began talking to my father about having read the Bible and being concerned with things that he wouldn't share. But my father was struck that here was somebody who was struggling with something very deep, very personal, that he couldn't talk about, had turned to the Bible for guidance and that, you know, that's a very lonely place to be and you know, and that was 1953, where, you know, everybody sort of beat their chest and I got this and underneath that was a lot of, you know, struggle, but you know, at the same time, what's interesting to me about this is that, you know the world is very, very hostile and very dangerous, and the number of interests against the United States out there, you know, are many, and so the CIA plays a really important role in gathering intelligence and identifying the threats. And so I am, you know, somebody who looks at the mission of the agency and supports its mission and then also understands that it puts a significant toll on certain of the people who choose that. It's a career, and that, to me, is sort of the interesting play. And it ends up being that I can play with. You know the genre.

Speaker 2:I can make it, you know, as all good books should be both entertaining and instructive, and the entertainment part is, you know the drama, the thrill, you know the plot, the excitement, and the instructive part is sort of the way in which individuals make moral choices.

Speaker 1:It's fascinating, while we're talking about complex situations, what were the complex parts of Riding Beirut Station and which parts float easily?

Speaker 2:The storyline came easily out of the research. The complex part was to develop the layered relationships between Annalise and the two men in her life Corbin, who's a journalist with whom she has a romantic relationship but at the same time hides who she really is, and Bauman, who's the Mossad agent with whom she is conducting this mission but who she also hides things from. And these two men are also circling each other for different reasons, and so she's having to sort of keep together several different identities and several different sets of facts. And to manage that as the author, without making it look like I'm pulling puppet strings, but making it sort of intuitive and coming out of the character took me a number of drafts because I wanted her.

Speaker 2:This is really her book, her struggle, and she in some ways is a very she enjoyed being this identity, this taking on this non-official cover identity. It gave her a sense of being herself, but at the same time she loses herself in it, and in the very last scene she's afraid to be vulnerable, she's afraid to show who she really is because she's used this nonofficial cover as a defense. And so where I left the novel is that she's having to go off because he's offering to help her, but she's not sure whether she wants to give up that selfish solitude that she'd become comfortable with.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I'm not going to blow the ending for anybody, but I was so glad that you bought in her vulnerability and you showed us that and also you showed another side to his personality.

Speaker 2:Well, they both had gone through bad relationships, marriages had died for different reasons, and so I think they were all you know. Their humanness came out. They were looking for human connection in a dangerous place.

Speaker 1:Well, I'm going to give you a compliment, and that is that you had me feeling the danger While I was reading the story. I couldn't help but wonder what it must have been like for Annalise to have to constantly be suppressing her emotions. That would be difficult, and that's what made her vulnerability at the end of the story so real, because I think she would have been scared of that. And I started to think if there was a decompression period for agents that they have to go through before they get back into their home world, the reality of coming home. There are a few times where I was very concerned for Annalise's safety. Okay, let's talk about publishing. I would love to hear your publishing story, from your first finished manuscript to finding an agent and publisher.

Speaker 2:Well, this is my sixth book and I've been with the same agent since the beginning and I've been with one publisher for the last four books, my first book the challenge there was to find an agent and what I did was to look up authors who I thought wrote this genre that I wrote in and see if they made a reference to or thank their agent in the acknowledgments. And I did find one, a guy named Olin Steinhauer, who was a wonderful writer and he acknowledged the Gernert company as being his agent. So I drafted a note query letter to David Gernert, who's the head of the agency, and said I love Olin's work and my work is a little similar. Would you like to take a look at it? So I got a note back saying yeah, we would, and that was very serendipitous, but it was.

Speaker 2:You know you can send off agent query letters and never hear back from anyone, because the people you're querying have nothing to do with the type of book that you're writing, and so I think you know, as a young writer, you really have to be smart about how you reach out into the publishing world. So I was very lucky and my agent, who is with the Gernert company, has been my agent since the beginning, and then he became the means by which we approached publishers. But I, you know, my advice to people is get an agent and make sure that it's a good agent and one that you have a good relationship with, and then that makes all the difference in the world.

Speaker 1:Just to make sure I have this correct. You queried one agent.

Speaker 2:No, I queried a few, probably three or four.

Speaker 1:Well, that's not many, and it's great that you had a yes so quickly.

Speaker 2:Well, the other thing, I guess the other thing. I think that it's important. You know, I went to an MFA program and people in MFA programs are taught to write literary fiction and a lot of that literary fiction is very good but it doesn't sell. So one of the things that I did was I chose a genre which is and I've made it into my own literary style but it's a commercial genre. You know, it's spy novels and, and I think one of the reasons I was able to get publishers is that I am writing fiction that sort of falls into a recognizable genre and publishers are all about making money. They're looking at a profit. Editors will try and find the best book, something that they can relate to and edit.

Speaker 2:But on the other hand, they're being judged by the number of copies of the books that they edit. They're sold into the marketplace. So I think you have to be realistic about what publishing is. It's a business that is intended to make a profit. It so happens that the business is sort of the art of storytelling that they sell into the marketplace. But it's still a business and I think you, as a writer, you have to be conscious of how an editor will see their effort to market the book. When they get a book, they'll put it into categories. You know, is this a murder mystery? Is this a cozy mystery? Is this a literary novel? And that's their job. And I think, as a writer, you have to be aware that that is what goes on when your manuscript lands on an editor's desk.

Speaker 1:Absolutely yes. Okay, let's talk about indie bookshops, in particular, two that have been on the show Otto Penzler's the Mysterious Bookshop and the Poisoned Pen bookstore, owned by Barbara Peters and I'd like to know why you feel indie bookshops are invaluable to readers, authors and communities.

Speaker 2:Well, I think for readers they're invaluable because when you go into a bookshop and I'm thinking about in a physical bookshop the people who are the booksellers are really knowledgeable about books. They read a lot. The reason they took that job is that they enjoy reading and they can be something of a conch shares for the browser. You can ask a bookseller well, I like this book, what's a book that's like it that I haven't heard about? And their recommendations can be very illuminated. At the same time, bookshops are really important for writers because they, as is the case with Otto and Barbara, they have readings and they actively promote the work of the writers who participate in those readings, and so it's. They sort of create a marketplace between the author and the readers of that author's work and they help project it into the world, which isn't the case with Amazon. Although Amazon sells a lot of books, it doesn't. There isn't a personal connection between the reader and the writer. If you're on Amazon, you know you get a variety of different reviews.

Speaker 2:Unless you know who the reviewer is, it's very hard to take it away and make a choice about it. But Barbara and Otto are also just remarkable people. Barbara celebrated 34 years with her bookshop and Otto has had at least that many years as a, as a publisher and a bookshop owner. You know they're in the in the industry there's sort of icons, there's sort of symbol of, you know, this gracious approach to bringing literature to their you know their many readers.

Speaker 1:Yes, indie bookshop owners and the booksellers within those walls are passionate readers. I'm into my fourth year of the bookshop podcast and I've discovered that many booksellers have PhDs. They just love talking about books, reading about books, sharing their knowledge of books with readers, and they have found that being a bookseller in an indie bookshop is perfect for them. And when we buy from an independent bookshop, we are actually giving back to our community. The tax dollars go back to our communities rather than buying online from that other place. Anyway, I love independent bookshops. I'm all about community and giving back to our community, so I love to buy from independent bookshops.

Speaker 2:Both Otto and Barbara are wonderful people and they've done a great service to, you know, the reading community and the other community.

Speaker 1:Yes, they're both wonderful people. Okay, let's talk about books. What are you currently reading, and is there a book you'd like to see more people reading, apart from your own, obviously?

Speaker 2:Well, I just finished Joseph Cannon's Los Alamos, which was his first book. I've read most of his books, but I've been. I started with the most recent ones and then I've gone back and it's a wonderful book. It's the book, his first book. It won the Edgar for Best debut novel. It's very literary. It's a murder mystery, it's a spy story inside a murder mystery and the premise is that you've got Los Alamos, which is a place that doesn't really exist in the map at the time it was a secret, sort of dead sound and a murder takes place and the question becomes so how do you pursue and investigate a murder in a place that doesn't exist? And it's an interesting premise. And he's a wonderful writer, very literary.

Speaker 2:There's a young woman, ilana Berry, who just this year published her first novel, which she happened to have worked in the CIA, and her first novel is just it's a wonderful, wonderful book, really well written, with very complex characters called the Peacock and the Sparrow, and I highly recommend that. And then you know the books I always go back to. The Ripley books, you know, are wonderful. Rebecca by Anthony de Maillet is just a wonderful book, you know. Again, the books that have attracted me are the books that are about character, sort of interesting, compelling stories where the central character draws you in a year. You sort of live the stories through the eyes of the character. Withering Knights, you know, another wonderful book. My wife teaches English literature so through her I get special insight into a lot of the classic literature.

Speaker 1:I'm sure that adds another layer to the stories. There was one other thing, Paul, I wanted to ask you, and that is if you can share with us a little about the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation.

Speaker 2:So Elizabeth is married to a Bulgarian and it was a result of visiting his family in Bulgaria that she became interested in Bulgaria, and the historian, which is her first novel, I think, is set there.

Speaker 2:So she fell in love with him and she fell in love with Bulgaria and as part of that she took some of the money that she got from the historian and developed a writer's program that has been around, I guess, now about 10 years, in which she brings four English or five English speaking writers together with four or five Bulgarian writers in a place called Sozopol, which is on the Black Sea, for a five or six day writer's conference every year and her goal is to sort of bring together the literature of Bulgaria with the literature of English speaking countries and to develop this cross-cultural relationship. And I was a participant in one of the Sozopol seminars, probably now 15 years ago, and it was a transformative event to be there with, in my case, three other Americans and then some Bulgarians. So she's just a one person ambassador for cross-cultural communication between Bulgaria and the United States and they broaden their remit a bit. But she's just a gifted writer and a wonderful philanthropist who's dedicated to the cause of translation and cultural exchange.

Speaker 1:Yes, you mentioned the historian, and I think I must have reread that book probably four or five times. Oh gosh, it's just such a beautiful, beautiful story. And speaking of wonderful stories, Paul, thank you so much for being a guest on the Bookshop podcast and I wish you all the best with your new novel, beirut Station.

Speaker 2:Thank you for a wonderful question and for having me on the podcast. It's been my pleasure and I highly recommend the Earl Morris the Pinging Tunnel. It's a really wonderful thank you.

Speaker 1:You've been listening to my conversation with author Paul Wittig about his new novel Beirut Station. To find out more about the Bookshop podcast, go to thebookshoppodcastcom and make sure to subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to the show. You can also follow me at Mandy Jackson Beverly on X, instagram and Facebook and on YouTube at the Bookshop podcast. If you have a favorite indie bookshop that you'd like to suggest we have on the podcast, I'd love to hear from you via the contact form at thebookshoppodcastcom. The Bookshop podcast is written and produced by me, mandy Jackson Beverly, theme music provided by Brian Beverly, executive assistant to Mandy Adrienne Otterhan, and graphic design by Francis Barala. Thanks for listening and I'll see you next time.