The Bookshop Podcast

The Bookshop Podcast

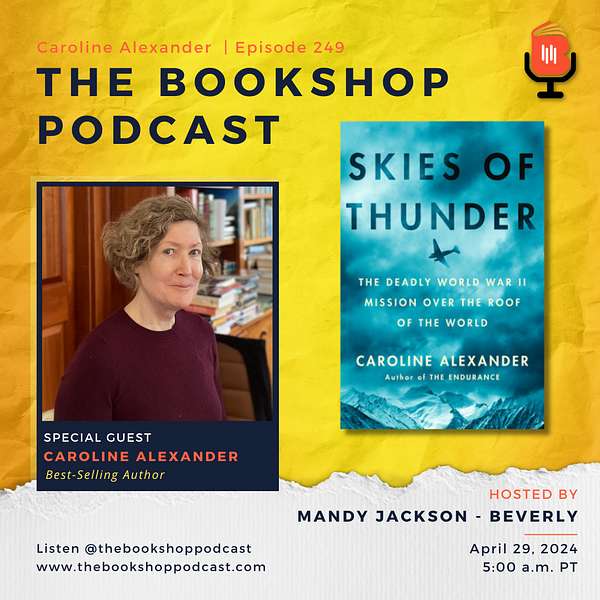

Caroline Alexander, Skies of Thunder: The Deadly World War II Mission Over The Roof Of The World

Embark on a historical odyssey as Caroline Alexander, New York Times Bestselling Author and acclaimed contributor to The New Yorker and National Geographic, unveils the lesser-known sagas of World War II's China-Burma-India theatre in her new book, Skies of Thunder: The Deadly World War II Mission Over The Roof Of The World.

With a background steeped in philosophy, theology, and classics, Caroline offers a rich tapestry of stories that captures the heroism and daunting challenges faced by those who shaped pivotal moments in history. Her transition from a voracious reader to a celebrated author is a testament to the power of classical languages in enhancing narrative precision, a theme that resonates deeply throughout our conversation.

The episode traverses the rugged landscapes of the 1940s, retracing the steps of untrained civilians who sculpted the vital Burma Road with nothing but rudimentary tools. Caroline's meticulous research paints a vivid picture of their struggle and the strategic importance of the road, inviting us to view their accomplishments as more than a military feat but an enduring emblem of the human spirit. The gripping accounts of the pilots who risked their lives over the treacherous "Hump" region come to life, showcasing their bravery in the face of primitive navigation equipment, daunting weather, enemy fire, and the Himalayas.

Amid the roar of engines and the call of duty, we hear the personal story of fighter pilot Robert T. Boody and gain an intimate look at the air transport command's overlooked dangers. Caroline's narrative explores the intricate web of allied relations, highlighting the strategic and geopolitical intricacies that shaped World War II's theatre in Asia. This episode celebrates the launch of Skies of Thunder and honors the legacy of those who navigated the deadliest skies with unwavering resolve. Join us to uncover the trials and triumphs that defined an era where courage soared above the clouds.

Skies of Thunder: The Deadly World War II Mission Over the Roof of the World, Caroline Alexander

Hi, my name is Mandy Jackson-Beverly and I'm a bibliophile. Welcome to the Bookshop Podcast. Each week, I present interviews with authors, independent bookshop owners and booksellers from around the globe, publishing professionals and specialists in subjects dear to my heart the environment and social justice. To help the show reach more people, please share episodes with friends and family and on social media, and remember to subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to this podcast. To financially support the show, go to thebookshoppodcastcom, click on Support the Show and you can donate through. Buy Me a Coffee. Okay, now let's get on with the show. You're listening to Episode 249.

Speaker 1:Caroline Alexander was born in Florida to British parents and has lived in Europe, africa and the Caribbean. She studied philosophy and theology at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and has a doctorate in classics from Columbia University. She is the author of the New York Times bestseller the Endurance Shackleton's legendary Antarctic expedition, which has been translated into 13 languages. Her other books include Mrs Chippy's Last Expedition, the Journal of the Endurance's Cat, the Bounty, the True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty, the War that Killed Achilles and her latest Skies of Thunder. Ms Alexander writes frequently for the New Yorker and National Geographic. Here's the synopsis for Skies of Thunder. Miss Alexander writes frequently for the New Yorker and National Geographic. Here's the synopsis for Skies of Thunder.

Speaker 1:In April 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army steamrolled through Burma, capturing the only ground route from India to China. Supplies to this critical zone would now have to come from India by air, meaning across the Himalayas on the most hazardous air route in the world. Skies of Thunder is the story of an epic human endeavor, one in which allied troops faced the monumental challenges of operating from airfields hacked from the jungle and taking on the hump the fearsome mountain barrier that defined the air route. They flew fickle, untested aircraft through monsoons and enemy fire, with inaccurate maps and only primitive navigation technology. The result was a litany of both deadly crashes and astonishing feats of survival. The most chaotic of all the war's arenas, the China-Burma-India Theatre, was further confused by the conflicting political interests of Roosevelt, churchill and their demanding nominal ally, chiang Kai-shek. Hi, caroline, and welcome to the show. It's wonderful to have you here.

Speaker 2:Thank you very much. I'm excited to be here.

Speaker 1:Congratulations on your new book, skies of Thunder the Deadly World War II Mission Over the the roof of the world. It is magnificent, thank you. I knew nothing about this particular part of World War II pertaining to Burma and I found it absolutely fascinating. And we'll get more into your writing of the book a little further on into our conversation. But congratulations, it's absolutely wonderful. The book is coming out on May 14th and I highly recommend pre-ordering this book. Okay, let's begin with learning about you and your diverse creative endeavors from professor, author and filmmaker.

Speaker 2:Well, I think of myself first and foremost as a writer, and that was what I had always, always wanted to be from. I can remember wanting to be a writer at age six. At that age who knows what that really meant, but I loved books and I was a voracious reader. I was very fortunate to grow up without television, so my sister and I read and read, and read, and somewhere along the line I read a. I went to a high school that had no structured I almost want to say instruction of any kind, but that's not quite fair. But let's say it was wide ranging, we were given a lot of latitude and somewhere in the course of that I stumbled on a translation of the Iliad by the great Richmond Latimore, when I was about 14, and it was life-changing. I responded to the story, the characters, the speeches, the whole sense of this being maybe quasi-historic in a very visceral way and decided that I needed to learn Greek to read the Iliad. Oh my goodness.

Speaker 2:I grew up in the United States and classical instruction is not normative unless one goes to sort of prep school type things. So I had to wait until I went early to university. So I had to wait until I went early to university, graduated from high school early a great part to get on with my program. But I was also becoming increasingly aware of how many authors that I read and enjoyed had been classicists. So I was very respectful of what a traditional Greek and Latin curriculum can do for a young writer, or a writer a yearning writer, let's say and I believe that the use of what I'd almost call these shadow languages, these languages that one is never going to really speak, is a very good training for word precision. It means you're translating for yourself in a private way, as opposed to learning, say, french or Spanish or German, which is going to be for public discourse. So I'm a great advocate for that for a writer. And then, when I came out of that, a friend and I put together, when I was at university in England, an expedition to collect insects in Borneo. We had undertaken it to travel the world and to see the world and we were very ill-qualified for it. It was really a game of bluff, and we raised money based on the name of Oxford as opposed to any skill, but anyway we went off to do it of Oxford as opposed to any skill, but anyway we went off to do it. And then when I came back and I was at graduate school at Columbia University for my doctoral studies in Classics, I had the urge to write about this experience and sort of poured it out over on these new phenomena called word processors that we had in the graduate room and showed what I'd written about the North Borneo expedition, as I had called it, to a friend. And long story short, the friend who was one of my professors had a very close friend who was a literary agent and he took the manuscript and about, I'd say, two, three weeks later I got a call that the new editor at the New Yorker, bob Gottlieb, had chosen this piece to be the first piece he would publish as editor of that historic magazine. And so suddenly I was a writer. While I always remember there was a sign in a student bar in Tallahassee, florida, where I grew up, that said 10 minutes ago I couldn't spell bartender, and now I are one. I couldn't spell bartender and now I are one, you know, and I sort of thought about that as my writing career that suddenly I were one and so I sort of balanced this creative so-called creative writing, if you will with my doctoral duties. And when I emerged at the end with my doctorate, to the satisfaction of my mother, I felt now I could embark on a freelance career, that I sort of knew the perils but I had a little bit of traction. So that was how I became a writer.

Speaker 2:But I carry classics with me a lot of the way, and very specifically the Endurance which was, if you will, my breakthrough book about Shackleton's extraordinary epic of survival, was very much written with the Iliad in mind. There was a kind of terseness of language where you rely on the flow of a narrative without having to ever get over. Homer is never overblown. There's actually, despite appearances, a very simplicity of language, very fast flowing, very straightforward in its way, but mostly the whole structure of that typically that story's always told ends with the heroic ending of the rescue of the men. But that would be like ending the Iliad when Achilles kills Hector. That's not where the Iliad ends.

Speaker 2:The Iliad ends on the mortal note, with Achilles alone in the tent and Priam coming to him, and the two men reflecting and acknowledging that they've had all this loss of life and they too are going to die. And I thought we need to know these were mortal men of Shackleton's, not just legendary heroes. And so I traced all the men, found out what happened to them after the expedition, which was sort of innovative at that time but I can say was directly inspired by the Iliad. So I lurched forward and I seemed to gravitate to epic stories, and Skies of Thunder is another epic story in my view. And you write them so well.

Speaker 1:Well, thank you. Where did the filmmaking come in?

Speaker 2:The filmmaking came in. I had a very dear friend of mine who was a very gifted documentary filmmaker, a pioneer named George Butler, whose best-known work was Pumping Iron, where he discovered Arnold Schwarzenegger oh my goodness. But he wrote. He had a very interesting background. He was a British American, grew up in Somalia, lived in Jamaica and just very curious and unorthodox and did beautiful documentaries with the kind of production value that people invest in feature films. And so I wrote for him specifically on a number of projects, including a documentary on the Endurance.

Speaker 2:Very tragically, to say, he died young 78, at the end of 2021, in the midst of making this wonderful IMAX movie about the tigers of the Sundarbans, the mangrove swamp area in Bangladesh and India, but a great, quirky conservation story, and I had been the writer of that and had been a sort of assisting as a producer. He was afflicted with Parkinson's and when he passed away, his producer and I finished the movie, which we've in fact just recently done. So I'm very cautious about claiming to be a filmmaker. I feel I was the partner and participant of a very specific, narrow range of projects. That said, I'm hoping now, with the producer, to do an IMAX for the Science Center venues one of these shorts, if you will, on the oracles of ancient Greece, which I think is a lot of new information and technologies. That could be very exciting to do that. So if that happens and it takes a miracle to make a movie if that happens I would more forthrightly claim to be a filmmaker.

Speaker 1:Well, that project sounds intriguing and the documentary you made earlier with your friend is that Tiger, tiger, yes, yes, it's out, isn't it?

Speaker 2:It was sort of unveiled at the Giant Screen Convention in just last fall and it's now getting leases, so we are anticipating it's being opened in two big theatres in Canada and then with these Science Centre movies. What I like about them is that they actually unroll over a very long period of time. They don't all come out at once all over the world in all the same theatres, so it would be some five years or so they would be unfolding. We got Michelle Yeoh to narrate, which was a real coup, just before she got her Oscar. So we had some good luck there.

Speaker 1:Good luck and exceptional talent To set the scene for your recent book Skies of Thunder. You begin by explaining the geographical place names of the era, which was 1940 through 1945. Myanmar is Burma, yangon is Rangoon and Thailand is Siam. In the second chapter you describe the intricacies and dangers of constructing the Burma Road. Can you expand on the urgency and the importance of building this road?

Speaker 2:The Burma Road is one of those great names. That is possibly the only part of the story that I had heard of before actually doing the research and writing the book. But if you had asked me what it really was, I don't think I could have told you. The Burma Road was begun, despite its name, in China. It was a Chinese nationalist initiative undertaken by Chiang Kai-shek and begun in 1934 following the defeat of his most dangerous foe, if you will, the communist. Chiang Kai-shek had many foe, but the group that he rightly feared the most in terms of being a direct threat to his personal power, were the communists, and he had had an important victory in the south of China, which had forced Mao and his followers out on their epic 6,000-mile trek to the north and will go directly to my capital, which at that point his new capital was Chongqing, in Sichuan province, on the Yangtze River. So work was begun on the road from the adjacent province, yunnan province, the most southwesterly province in China, towards to the eastward, to Chongqing, his capital, and that was done fairly straightforwardly. Then he began on the second leg, which only advanced about 100 miles, and this was westward, towards Burma, and in fact it's the westward part, it's the part from Kunming which eventually did lead to Burma. That became the classic Burma Road, a route of about 700 miles or so when all the quirks and turns of the terrain were taken into account.

Speaker 2:But the road languished after this initial start and then, with new urgency, was begun again in 1937 as the Japanese threat, which Japanese had been in Manchuria since 1931. But now there was renewed Japanese activity and one by one the coasts of China's great long coastline were being. The ports along the way were being captured and held, and China began to see that it could in fact be blockaded. So this vast country, but with a shoreline that's tied up, didn't leave very many routes of access from the outside world, and the other routes one coming in from the north, from what would have been the outlying part of the Soviet Union, was essentially impractical, beings very, very long and very, very difficult. So now the Burma Road, a route into Burma, becomes a kind of point of not just internal military strategy but really a kind of route of survival. And so this becomes a vast enterprise where all along this route from Kunming and Yunnan province, which was considered within China to be a very undeveloped backwater province, with many peoples along the way, who were not Chinese speaking, were not even ethnically Chinese, and one of the fascinations to me of learning about this was just to discover how many different peoples lived along this route as recently as the late 1930s, when the road is being built.

Speaker 2:Late 1930s, when the road is being built, and so it was built by civilians.

Speaker 2:They had some professional engineering oversight, but the actual manual labor and it was manual, with very few tools was built by the peasantry Chinese, all the people who'd really not been conscripted, so children, women, old men, many of them in undernourished because of the terrible poverty in China, and particularly that province at the time. And so it's this extraordinary spectacle of hundreds and thousands of these civilians being, you know, dutifully walking out to their levee points where they had been told you know you need to be at this place on this time and you're going to be responsible for building this amount of road. And then they build it. And the terrain encompasses some of the great river gorges on Earth, the Salween and Mekong River, for example, these extraordinary mountains, jungles, forests, and it's a kind of surreal conjuring. There's a very good account of it, given by the managing director, who gives the sort of eyewitness as it unfolds and you have men hanging from thread-like, not even scaffolding, just ropes off cliff faces. They had no dynamite, so they used firecrackers.

Speaker 1:That part of the story fascinated me At every roadblock, so to speak. Their ability to devise plans to continue is extraordinary.

Speaker 2:It's this continual improvisation faced with rock cliff faces. And how do you make a road? They're trying to sort of gouge along the side of the cliff and so they have to create this kind of literal inroad to wind around the cliff face, and all they have are chisels and hand tools. So thousands of they figure out that firecrackers have enough little gunpowder to make little pitiful explosions that help in the loosening of this rock. And so these thousands of squibs are placed, you know, one by one, into the rock face and lit, and then there's a little bit of tumbling and then they hammer that out, but all the time, you know, great peril of their own lives, sort of dangling on these makeshift lines. Then they come to the great rivers. How do you get a bridge across a river? Well, the first thing you do is you have men strip down, tie cables around their waist and swim a mile across the raging river and when they drown, then the next wave comes up and you just keep coming until somebody makes it across and then they pull that string and the cable attached to it and you have the first sort of beginning of a structure across across the river.

Speaker 2:One of the more horrifying things that happened is, as the road began to be completed, these vast hand-chiseled stone rollers, weighing you know sometimes many tons, were then hauled over the broken pebbles and gravels to kind of beat it all down. But these were also, if you will, new technologies and there are counts of people, particularly children, just not understanding that when you come on a downslope, these behemoth rollers are going to take on a life of their own. And there are these horrifying stories of people, particularly the children, running gleefully ahead of these rollers, like it was a game, just get crushed in the past. I mean just an extraordinary account of this remarkable road built by people who, as several sources pointed out, had never, in the course of their own history, ever seen a wheeled vehicle. So it's going to be a road for lorries carrying supplies, by definition, but the people's building it have never seen even a wagon. All transportation was done by foot or pack ponies.

Speaker 1:This seems like a perfect place to talk about the Lolo women and the Pendulum women. I found your descriptions of these two groups of women both charming and sad.

Speaker 2:So again, mr Tan, who was the managing director of this enterprise, wrote a wonderful book, a very small book which you can find on used bookstore sites like Abecom, called Building the Burma Road, and he gives a wonderful account of having to negotiate as they travel, moving towards the Burma border, westward towards the Burma border, passing through all of these different peoples, and each one has different customs and different habits and different taboos and different preferences, and the Chinese engineers sort of have to negotiate with them one by one and often accommodate their own preferences. So the Lolo people were known as the tiger people, very much feared by everybody, not just people within China. But when the Americans move in with their air mission, there's actually a story of some downed airmen being kidnapped by them, which is a whole kind of other side story. But they had a very fierce reputation. But nonetheless, the Lolo women appear and their costume is this kind of gleaming white tunic, which becomes important because their strong preference is to work in the dark and they liked this because it meant they could care for their families during the day. Their children have accompanied them and then they can work at night. And so the director describes seeing the women you know by their gleaming clothes in the moonlight, working at night where all the men were afraid of working at night because this is when the predators, uh, tigers, so forth, come out. But, as uh the managing director says, you know, the lolo women were said to be dead shots with the bow and arrow. So I always loved that kind of sort of glimpse into these. You know, women who were so motherly that they wished to care for their children but would go out at night, you know, prepared, as it were, to do battle. But the pendulum women were the Shan women.

Speaker 2:Even further west, as you move into Shan country, which is straddles China, and now into Burma, the country and people were known as by all travelers as being exceptionally beautiful and the country had a sort of wonderful climate and a lot grew there very easily and there was a kind of more indolent way of life.

Speaker 2:And it was also, it has to be said, a place with fierce malaria. But when it came to trying to negotiate with the Shan women, who were, of all the peoples along the way, the least conditioned to this kind of hard labor, but they knew their rights, as it will, as few will, and they knew their preferences and their strong preference was that they wished to carry the rock debris in baskets balanced picturesquely on one shoulder, I think, like if we've seen illustrations of ancient Greeks with amphora carried on their shoulder, sort of very graceful for a, you know, carried on their shoulder, sort of very graceful whereas the more practical way and conventional way to haul off rocks was by balancing a pole across your shoulder with baskets balanced at each end. But they remonstrated with the director and they said if we do that, we can't sway when we walk and we're known as the pendulum people. Uh, we must sway when we walk and we're known as the pendulum people. We must sway when we walk.

Speaker 1:And so the exasperated managing director, you know, acquiesced to their demand and the shunned women carried their baskets gracefully on their shoulders, and this speaks of the diversity of the people who worked on the road and, as you said earlier, the poverty in which they lived.

Speaker 2:They were living in poverty and they were levied. I mean, it has to say that this was a came down as a mandate from the national government. You know that they had to comply.

Speaker 1:Yeah, they didn't have much of a choice. Now you've written about the dangers the workers faced severe weather, mud, treacherous heights, mosquitoes, other disease-spreading insects and, of course, predators like tigers. Now, apart from Mr Tan's book, how difficult was it to find primary source information for your research?

Speaker 2:On this particular aspect of the larger story. This was one of the least difficult parts. The Burma Road attracted a great deal of international attention at the time. It was a huge, vast human enterprise. It was a moving story, it was a lifeline being boiled by China's own people in the most kind of heart-rending and hardscrabble way with their bare hands. And so there was both a kind of sentimental interest in this story as well as a more focused interest, which is how well is this going to work? Is this, you know, wars looming ahead? These kinds of supply lines are going to be of interest.

Speaker 2:And so there was a great deal of, I'd say, more academic study from the British side, which looked at things like tariffs and cargo numbers and the statistics and how much was actually getting through. And from the American side there was perhaps more sentiment. For example, national Geographic magazine sent a team to ride the Burma Road and in fact they were never able to finish it because they got caught by the monsoon. And therein lay the most cautionary part of this, which is that how effective really was the Burma Road as opposed to a grand symbolic gesture? But anyway, the long and the short is that, from various points of view. With few travelers who even rode the road, intrepid people who went in early, it was possible to get a lot of detail into that particular part of the story.

Speaker 1:And when did the research become more difficult In?

Speaker 2:terms of moving chronologically through the story. The Burma Road was one of the first parts I really dug into, and so that material seemed to come very readily. The rest of the book, I'd say that there was both too much information from some quarters and not enough information from others, which I suppose is the way that all big research projects goes. But, for example, the uh us air force archives have a plethora of, I mean thousand, tens of hundreds of thousands of pages of material, all of which was digitized and sent to me during the pandemic and this gives the kind of raw logistical data of the campaigns and of the building this air route and so forth. Then there were lots of memoirs privately published recently, privately published by sons and daughters of participants who'd found their dad's diary and realized that they could, you know, wanted to get it out. There were lots of memoirs from particularly British who'd lived in Burma or in Northeast India during the time.

Speaker 2:I love books that are out of print, so it was fun to just track them down. In fact there's a wonderful source you have in Australia called Asia House, which specializes, as its name sounds, in obscure books relating to Asia, and I found a number of wonderful fights there. But I'd say the part that most frustrated me was, as the story progresses, there is a big role paid by the Chinese. Really, peasants who've been recruited is too kind a word who have been yanked into service to serve in the army that's eventually going to American-led army, that's eventually going to go into North Burma, and the experience of these people is largely told through the eyes of the optimistic eyes and language of the American trainers, and it was very tough to find any kind of voice from those people as to how they actually viewed the experience. So that was a big, to me, dark hole that I was never able to fully penetrate.

Speaker 1:And that segues beautifully into my next question. On page 106, you write about the inadequacies of navigational aids on the planes being used to fly over the hump. Can you explain where the name the hump derived and the terrain that made this area extremely dangerous to navigate? But before you do, there's something I wanted to talk about at the beginning of the book. In the prelude, which to me had the book reading almost like a thriller, Prelude, which to me had the book reading almost like a thriller you give excerpts from pieces written by pilots talking about their experiences flying over the hump and they are remarkable and it makes narrative nonfiction wonderful to read, exciting to read.

Speaker 2:There are a number of factors that made this terrifying, and that's perhaps unusual is how layered the difficulties were. So the hump specifically refers to this is the air supply of China from India, largely run by the US Air Forces, although there are other participants. There's a commercial American-Chinese commercial operation that did a valiant service called the Chinese National Aviation Corporation, and there were some RAF and Australian pilots also, by the way who participate in it. But largely this is an American operation and they start from northeast India in the province of Assam and fly to the nearest point in China, which is, or the nearest feasible point in China, which is Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, which is the province closest to Burma. So in the middle of this there is Japanese-occupied Burma and in the middle of this is the Japanese. Not just Japanese-occupied Burma, but one of the great, vast jungle areas of the world.

Speaker 2:The hump refers to a ridge along this route that specifically rises between, if you're coming from the West, from India, between the Salween and the Mekong River and in the Hengduan Mountain, larger Hengduan Mountain range. But that very narrow ridge came to stand, was named the hump, just with kind of airman slang, and was named the hump just with kind of airman slang. We're flying the hump, we're flying the rock pile was another phrase that they would give, but it also came to stand for the entire route. So flying the hump essentially meant the whole route. What made this so difficult? It's hard to even know quite where to start, but let's start just with the route. The route, if flown absolutely correctly, never really had to surmount anything higher than about 15,000 feet. There was a way point along route, lycian Mountain, which rose to about 18,000 feet, which one flew. It was a landmark to sort of turn the corner to the southeast, but that was about the height that the aircraft alone had to accommodate. However, on a clear day, visibly on all sides of this route, well within a hundred miles, were mountain peaks of the Himalayas which rose vastly higher.

Speaker 2:So the first thing that was imperative was that this route had to be stuck to pretty closely. If you deviated you would be in great danger. The first challenge was that the maps and charts themselves available when this operation began, which was in 1942, were very, very faulty, and there were errors in every direction. Sometimes mountains ranges were listed higher than they actually were, sometimes they were lower, and so that in itself was very, very destabilizing. The second point is that there were initially, particularly when it began, no navigational aids en route whatsoever. So you had a compass and a heading and a kind of airspeed indicator, but there were no air traffic control. There was initially just one beacon that was put in I think it was January of 1943, which was just a kind of allowing you to have a landmark as you headed over the Burma jungle, but very much pilots were flying essentially like ships sailing by dead reckoning. Later on, in the course of the, as this was sort of developed out, there were radio stations, but these were mostly at the destination. They weren't along the route, because along the route was Japanese occupied Burma. So you would get some aid as you came in, maybe within 200 miles if you had perfect conditions, more likely within 25 miles if conditions were less than perfect as you came in towards your destination.

Speaker 2:But in the midst of all of this was the what was arguably the worst aviation weather system in the world, and this was a diabolical convergence of both very moist low systems coming from the Bay of Bengal on the west and the South China Sea on the east, then combining with these very diabolical dry, cold winds that come rushing down from Tibet and from Siberia, and the convergent meant this kind of chronic maelstrom of turbulent weather, in addition to which you have the mountains, and mountains, as any pilot would tell you, can cause what's called mountain wave effects, which is when high winds slam against the mountainside and then create a kind of wind shear that can even today, you know, one has to be very wary of, can flip planes, invert planes, aircraft. So you had these weather conditions, on top of which you had a monsoon kind of climate, so there were these periods of just intensely solid rainfall, and on top of all of that, the thing airmen perhaps feared most of all was ice, and the ice conditions were extreme. They not just encountered a long route, but at vertically, so from 9,000 feet all the way up to 26,000 feet. Which brings us to the final factor, which is the capabilities of the aircraft.

Speaker 2:At that time these were not aircraft like today where we can fly from, you know, sydney to Cairn at 26, 28, 30,000 feet, 40,000, 42 if you're flying other routes. These had a kind of cruising ceiling of about 20,000 feet, and some of the later aircraft could go up comfortably to 26, 28,000 when empty. But you start to put all of that together 28 000 when empty. But you start to put all of that together and imagine being a pilot who takes off and expects to fly, solid instruments all the way, with very few navigational aids, with winds that press him off course, navigating by dead reckoning or the seat of his pants and knowing that any margin of error means that he may be landing on a mountain peak, somewhere that he can't see.

Speaker 1:It must have been terrifying.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:And I enjoyed the pilot's backstories that you put into the book. Did you happen to read Robert T Booty's book Food Bomber Pilot?

Speaker 2:Yes, that's actually one of my, I'd say, most valuable sources. Bob Booty was a pilot who came over to India, initially to be a fighter pilot and through he had fallen in love and become engaged with a nurse on the long sea voyage over and once he was sort of established in his barracks, his very makeshift basher barracks in India, he decided he would just fly on over to visit her. And I have to say I think fighter pilots tend to be, I think it's necessary that they're cockier than other pilots. I'm proud to say my partner was a former Navy pilot who flew in Vietnam, and I think he would acquiesce to that actually. But anyway, bob Booty felt that he had clearance to go over and see his fiancee and it turned out that the authorities saw it very differently and so he was charged with going AWOL and as a result of which, when the dust settled, he had been demoted from being a fighter pilot to an air transport command pilot. Now, this is of interest for many reasons. One then Bob Booty's wonderful diary starts tracking the story I'm tracking, which is of course air supply and the hump and so forth, but it's very, very indicative in what low esteem the air transport command pilots were held, because to be demoted to one of them is a very eloquent way of saying you've been put down with the people we regard as the lowest of the low, and so I think one of the things that was very demoralizing from the outset was that, you know, the fighter pilots were top of the totem pole, if you will, and then below them are the bombers, and then below them maybe the evacuation planes, but at the very, very bottom are just cargo pilots who are truck drivers in the view of the kind of established hierarchy. And indeed the acronym of the Air Transport Command, atc, was cynically used by people outside the services, saying it meant allergic to combat. So they were sort of looked down upon as being non-combat pilots, and yet here they were flying this inherently very, very dangerous mission, very, very dangerous mission. So Budi is a wonderful voice in that you see him having to adapt to this task for which he's not trained. He was obviously a very skilled pilot and survives the war, although has an accident really not of his making at the very end that takes him out of service. But it does underscore another point, which is that the pilots who were funneled into the Air Transport Command were the least trained. The most trained pilots are going on what are recognized as the big, important missions in Europe, in North Africa, as fighters and bombers.

Speaker 2:There are stories. I actually interviewed one pilot, a lass who's passed on since I spoke to him, but he described arriving and being told to collect with a friend, a C-46, which was the new, bigger cargo plane that had just come into the theater, and had a lot of problems with it, by the way. And they arrived. They had known it was a c46 and they arrived to find it and they had never seen one before, they had never been instructed in one before, and he said we literally had to figure out how to open the door. And then they got in and read the manual as they taxied sort of desolatory back and forth and then he flew it first to Calcutta where, just because it was a new plane and it had to go there and that was the protocol, and then took it over the hump.

Speaker 2:But there are stories of pilots arriving with 25 hours of instrument training, which wouldn't get you a pilot's license I don't think today and yet they were then thrown into these severe conditions. So I think the level of fear was not just because the situation was inherently difficult, but because, as one executive said, look, the kids are flying over their head, was how he put it. And so the protocol was the more seasoned pilots would fly and the junior just arrived pilot would sit as co-pilot in the right seat a certain number of hours, but that was their training and sadly, many of them didn't make it home.

Speaker 1:In your book you quoted something like 600 planes are littered across this flight path. That is an extraordinary amount of planes.

Speaker 2:The way I came on this story was I was on assignment for National Geographic magazine on a story about tigers, and I was in the north of what's today Myanmar, in this amazing place called the Hukong Valley, which is today holds the world's largest tiger reserve and is a spectacular wild jungled area, but was in fact that area over which the pilots were flying? And very few people go into this area today, really only wildlife officers or poachers. And so I was talking to the wildlife team about their stories and so on, and there were some Naga villages scattered throughout this and they had these very strange metal fences around their vegetable plots, and when I commented on them, the wildlife officers said, oh, they cut those from the fuselages of the cargo planes in the jungle. And that was how I learned of the story. And they one of the officers said that he'd been on a patrol some years before and come on a downed aircraft, he and his team, which had the skeleton of the pilot still strapped into the left seat, and I couldn't believe this that cargo planes just would vanish, be buried in the jungle still. And then, when I came back to the States, I looked into it and I was told that the estimate is about 600 are still undiscovered and that I would say, and I think most people would say, is a very conservative figure.

Speaker 2:The record keeping was very spotty, particularly during the first year or so of this operation, and other records speculate that there are as many as you know, more like 1,200. But we'll never know that they just people, the planes either. Sometimes they were found after a crash, because you would see an explosion and smoke and a pilot flying over could spot it, but often they just vanished just into silence. And this is something one of the pilots wrote about in his memoir. He said you know, we'd all wait and wait for this plane we knew was meant to come in and we'd hope it had been diverted to another airfield. We'd hoped it might have stayed overnight somewhere, but then it never appeared. Never appeared, just silence. So that was the fate of some aircraft and another others. Were the crews bailed out? If they got lost, if they had engine trouble, if they would run out of fuel because they were lost, they would parachute out and the aircraft, you know, would drift on to crash somewhere.

Speaker 1:Maybe found, maybe not found and if we just think about that figure for a moment, 600 to 1200 planes, that's a lot of money the US had invested in this region of the war. And that kind of leads me to this question, because I'm interested in your thoughts on how did British colonialism affect what the Americans were wanting to do in this geographical area of World War II, and how did Churchill and Roosevelt differ and thought similarly about China at this time?

Speaker 2:I would flip it around, I would say the driving dynamic of this hump operation was what the British regarded as an American obsession with China, and it could not be shaken. It was very unclear quite what the objectives of this great heroic airlift was. So at the very beginning, from correspondence that came back from advisors, american advisors, who were sent over to sort of examine the situation of China, as you know Japanese have the war has already begun, if you will, in China, earlier than it will, if one considers the Japanese invasion of China to be, you know, part of the larger war as it eventually becomes. So American advisors were going over and they come back with actually brutal assessments of Chiang Kai-shek, both as a person, as a leader and as capabilities. But they believe that having the japanese continue to occupy china is good for the wider war effort because it will tie down those forces as in in a kind of occupying situation which could otherwise be unleashed to cause harm, particularly as the pacific war, you know, looms into focus. So the first kind of objective is that this will keep China from collapsing, and by collapsing essentially they mean selling out to the Japanese. At the same time, every advisor from every nation understood clearly that Chiang Kai-shek would never sell out or fall to the Japanese, that his own grasp of power, his own thirst for power was so strong he would never put himself in that position and also his hatred of the enemy was very real. So this collapse that's always threatened and which Chiang Kai-shek threatens the allies with too, that if he doesn't get this loan, if he doesn't get this a billion dollars worth of gold one of his demands is, if he doesn't get 10,000 tons a month over the hump in supplies, china could collapse, her morale would collapse, and it's always a threat that he continually wields.

Speaker 2:But it's unclear really what that would have entailed. And certainly a lot of the airmen actually who had come to know China said, you know well, even if they did, there were so many other warlords, there were so many factions, there were also the communists that it was never as if the Japanese could have just, you know, bailed out and got somewhere else. They were going to have to be in it one way or the other. So the first sort of sketched objective is that this holds down the Japanese in the war. But the second objective, which is stated with much more clarity by the Americans, and by Roosevelt in particular is that the end of war objective is that China will be this great democratic ally and particularly close to the United States, that the United States having shown all this goodwill and fought as an ally, as, if you will, with Chiang Kai-shek, that the inevitable result afterwards would be these four powers Britain, the United States, soviet Union and China but that China would be very firmly attached and beholden to American leadership and, in other words, a very close and I would almost want to say cynically manipulated ally. That was the view, and Roosevelt prided himself on his knowledge of China. His maternal grandfather had made a fortune in tea and opium in China and he liked to refer to this and he would tell people you know, I have 100 years of history of China myself and my family, so there was a kind of sense that he knew what he was doing and genuinely looked forward to this kind of great new balance of power which, amongst other things, would diminish the European and specifically British power in the East and would increase American power in the East by being so closely allied to China.

Speaker 2:So a lot of geopolitical maneuvering and objectives here, and so out of this comes all of these campaigns, the Hump campaign, the land campaign through Burma, and the British had an entirely different view of the value of China. They did not believe in Chiang Kai-shek, they did not believe in the fighting power of the Chinese troops and army, which they knew to be starved of both food and supplies and leadership often, and they did not believe in this vision of the post-war kind of reality. And indeed there's some memos that are written by sort of British-Chinese experts that said look, there's nothing we can do. There's going to be a civil war and it's quite possible that the communists, who have, you know, this number of force behind them and better policies and so on, are going to win and there's nothing we can do about it. The British well, what can you do? Based on very deep analysis and the American optimist we can't do nothing, you know. Of course we must try, of course we can make it work, and bold big ventures are done by that latter view. You know, building the hump, airline, I guess, sending people to the moon, you know all of these impossible things. So one can admire that can-do, must-do kind of spirit that I think is very American and very entrepreneurial American. But sometimes reality thwarts that best optimism, as it clearly did in this case.

Speaker 2:It's safe to say that the British and Americans, who were allies, were also deeply suspicious of each other's motives, particularly in this particular theater China, burma, india the Americans were intent on fighting a land war, and the reluctance of the British to be dragged into a land war in Burma made the American think that the British wanted the Americans to fight their war, whereas in fact I think Churchill would have been happy to have had no Burma campaign and to have said simply look, the Japanese are in there, we cut off their supply lines, they're going to starve and have to retreat or just die in the jungle outposts.

Speaker 2:If we blockade Rangoon, for example, on the one hand, and we're on the other side in Siam, we can hold them down. So it's a fascinating conflicted sort of situation amongst these close allies in what is already an entirely chaotic and very difficult theater. But it's safe to say that I think the one thing Churchill and Roosevelt did agree on was ultimately on the value of one the air supply and two air bases being built in China for a projective offensive. That, by the way, never happened. Certainly the British voiced support for it, churchill voiced support for it, but I believe that actually they only voiced support for it because they thought it would deflect attention from a land campaign. I'm not convinced the British actually really supported the idea of any of these very messy campaigns, whether it was the air operation in China or the air supply to China.

Speaker 1:I'd love to talk about your research and writing process. You mentioned that you began writing this book or researching this book during the pandemic. Can mentioned that you began writing this book or researching this book during the pandemic. Can you talk a little about this and the amount of time you spend on research before starting to write?

Speaker 2:Yes, I was very fortunate to have got the commission ahead of the pandemic, because it's wonderful to have a big juicy project while people are on lockdown. And I found that the archives that I needed were very accessible remotely. I mentioned in particular the Air Force archives in Alabama, for example, that were very timely in sending out these reels and reels of material timely in sending out these reels and reels of material. You know, as a freelancer I have the luxury of deciding what my next, or hoping to decide what my pitching my next project in any case, and I had done this based on my experience in the Hukong Valley of coming away with this vision of these fences cut from the fuselages and so on and very little else. I knew nothing. I had had a great aunt who had worked in Burma, as it was still called for the World Health Organization, and so I love the name of that country and I had sort of been drawn to the country and I love traveling in modern Myanmar at that time.

Speaker 2:But the things that I thought I knew well, even about the Pacific War. I realized how sketchy my knowledge really was, and so there was a wide amount of reading just to get the context of the theater, of what was going on, of who was who, of what the objectives were, before one could even get down into the details of the hump. But the only thing I can say is it's some of the most fascinating reading I've ever done. It was from memoirs of people growing up on tea estates in Assam to these extraordinary accounts by the pilots who survive walkouts, you know, after they bail kind of extraordinary background of the big powers playing out, both grappling for the future after the war and hoping to actually win the war. It's just amazing stuff.

Speaker 1:Yes, it is Okay. What are you currently reading?

Speaker 2:Well, one thing I'm doing is mopping up on things that I never quite read thoroughly. My favorite is the diaries two-volume published diaries of General Henry Arnold, known as Hap Arnold, who was the chief of staff of what was then the US Air Forces. I love these diaries from the era and of course I read closely the parts that pertain to my story. He was building the American Air Force really from the start, not quite from scratch but almost from scratch, and there are many theaters of war that he was having to be involved in, every detail of it, and it's just a very uncomplicated, very nuts and bolts type of writing, very refreshing, and I'm enjoying that.

Speaker 2:Next, what I'm just starting, is a wonderful book by a scholar of the Aegean and I guess you'd say the Aegean and Greek Bronze Age, called Geoffrey Emmanuel, called Black Ships and Sea Raiders, which is about the well, it sounds very dry but it's quite interesting the sea peoples and the migrations that brought down the Bronze Age, and so it very much overlaps with the Homeric narrative. So I'm very interested in that. And finally, there's a writer of fiction I haven't read in a while, but Henry Williamson, probably best known. He wrote Tarka, which was a sort of beloved children's book in England but he had been in the First World War and wrote a 12-volume autobiography that's sort of disguised as fiction and I'm about halfway through and I had to put it aside for this book and I'm going to go back to that.

Speaker 1:It sounds like you have your reading cut out for quite a few months the rest of my life. I think, reading cutout for quite a few months, the rest of my life, I think, caroline, you are a vessel of knowledge and, as the text on the back of the book says, skies of Thunder is a masterpiece of modern war history, and I'm always surprised at how many people are interested in planes from World War II. Yes, me too, actually. In planes from World War II. Yes, me too, actually. Thank you so much for being a guest on the show, caroline. It's been a pleasure chatting with you, thank you.

Speaker 2:Well, thank you, and I have to say that, as you know, my great friend Lynn Cox, who you interviewed earlier, had told me that this would be the best interview I'd had, so I just wanted to pass that along also. Thank you very much.

Speaker 1:Well, I hope you enjoyed this conversation, because I certainly did.

Speaker 1:Yes very much. Thanks again, caroline. Thank you Bye-bye. You've been listening to my conversation with Caroline Alexander about her new book Skies of Thunder the deadly World War II mission over the roof of the world. To find out more about the Bookshop Podcast, go to thebookshoppodcastcom and make sure to subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to the show. You can also follow me at Mandy Jackson Beverly on X, instagram and Facebook and on YouTube at the Bookshop Podcast. If you have a favorite indie bookshop that you'd like to suggest we have on the podcast, I'd love to hear from you via the contact form at thebookshoppodcastcom. The Bookshop Podcast is written and produced by me, mandy Jackson-Beverly, theme music provided by Brian Beverly, executive assistant to Mandy Adrian Otterham, and graphic design by Francis Ferrala. Thanks for listening and I'll see you next time.